Dead collaborators, indie horror, and turtles all the way down

an interview with Walter Woods, developer of Dark and Deep

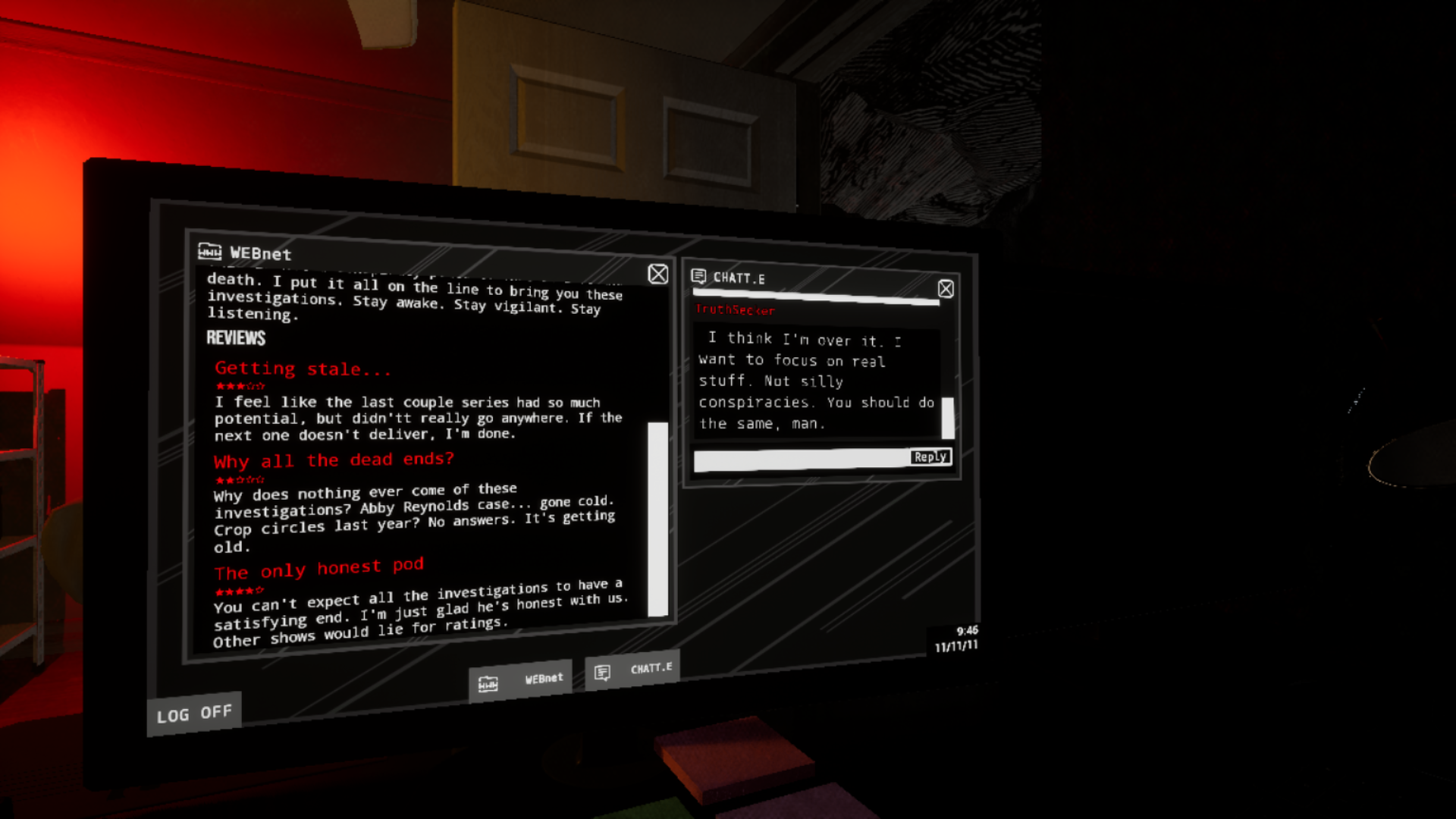

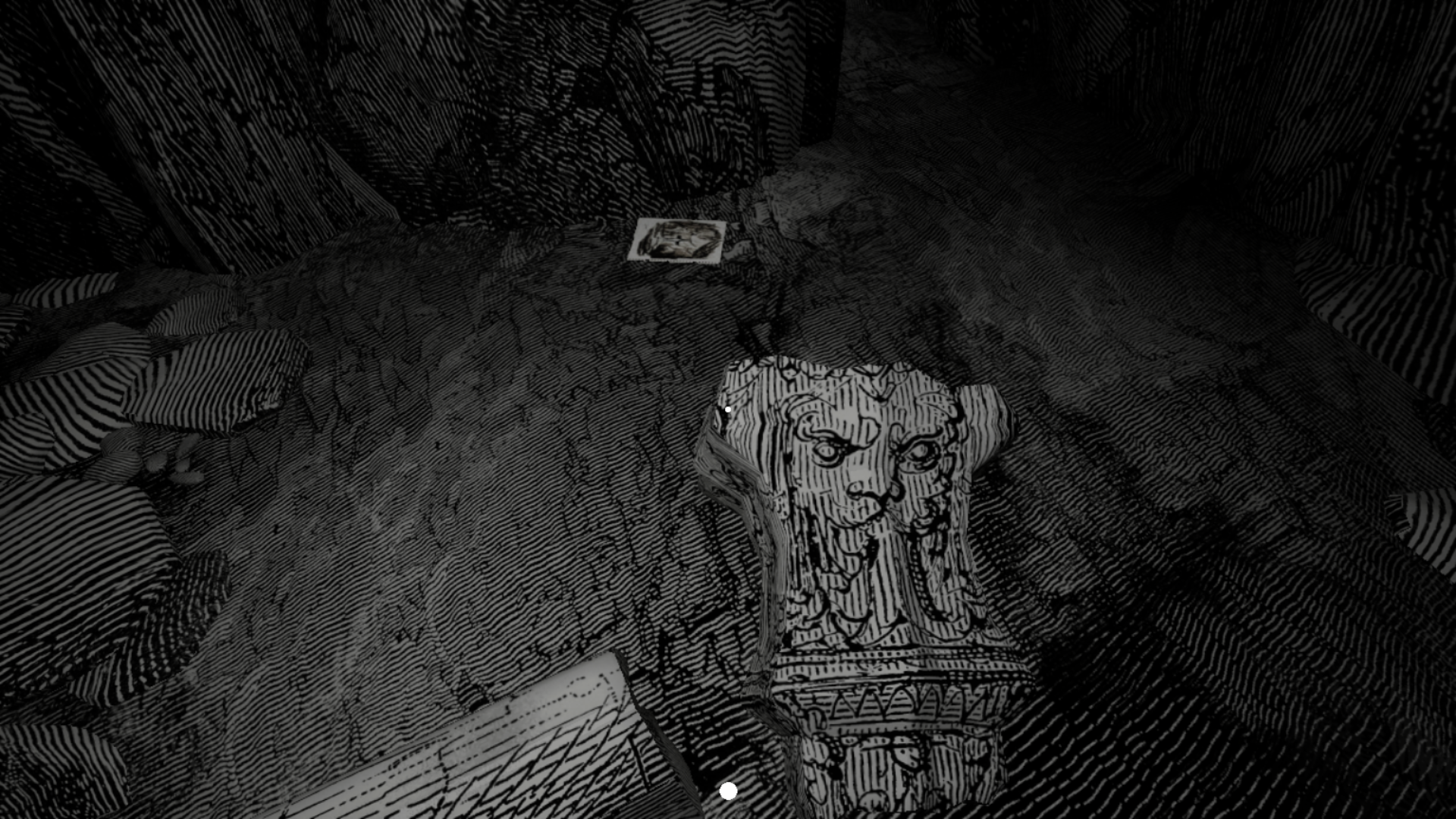

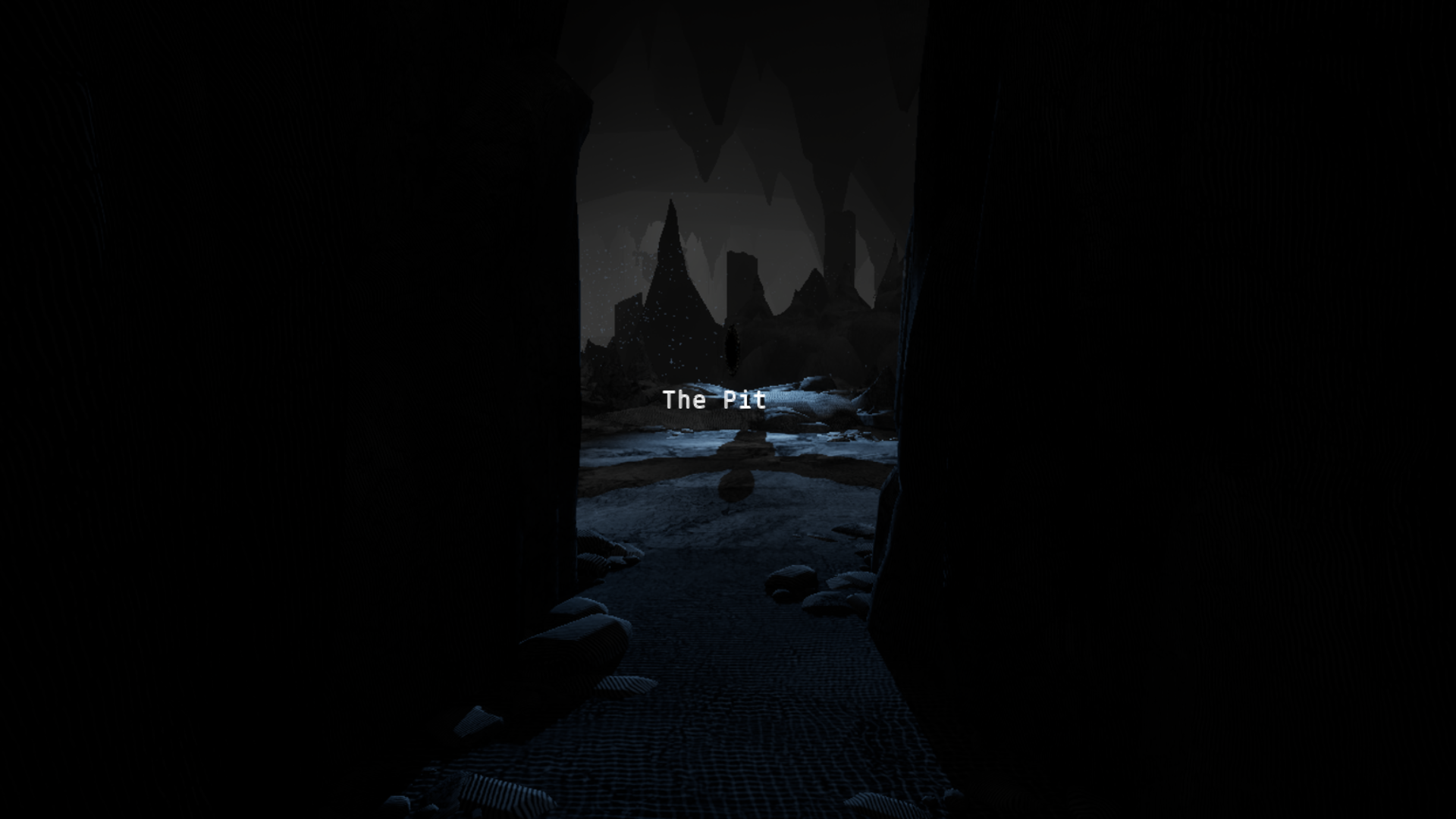

Upcoming indie horror game Dark and Deep follows Samuel Judge, an increasingly isolated conspiracy-theory podcast enthusiast, as he descends into a nightmarish, monochrome world. Wielding picture frames to find hidden objects and horrifying creatures, Sam must fight to survive, solve puzzles, and find small embers to light his path to freedom.

This is, to put it mildly, my cup of tea. I reached out to Dark and Deep's developer Walter Woods for an interview, and, fresh from PAX, he told me about the challenges of solo development, staying motivated, and collaborating with dead artists.

'I've always loved Doré's works, since I've been aware of it, probably, since I've been young. But I think I love it because I like the literary work that it was illustrating. So I've always been a fan of like, Paradise Lost, Divine Comedy, the Bible, I always love that stuff.'

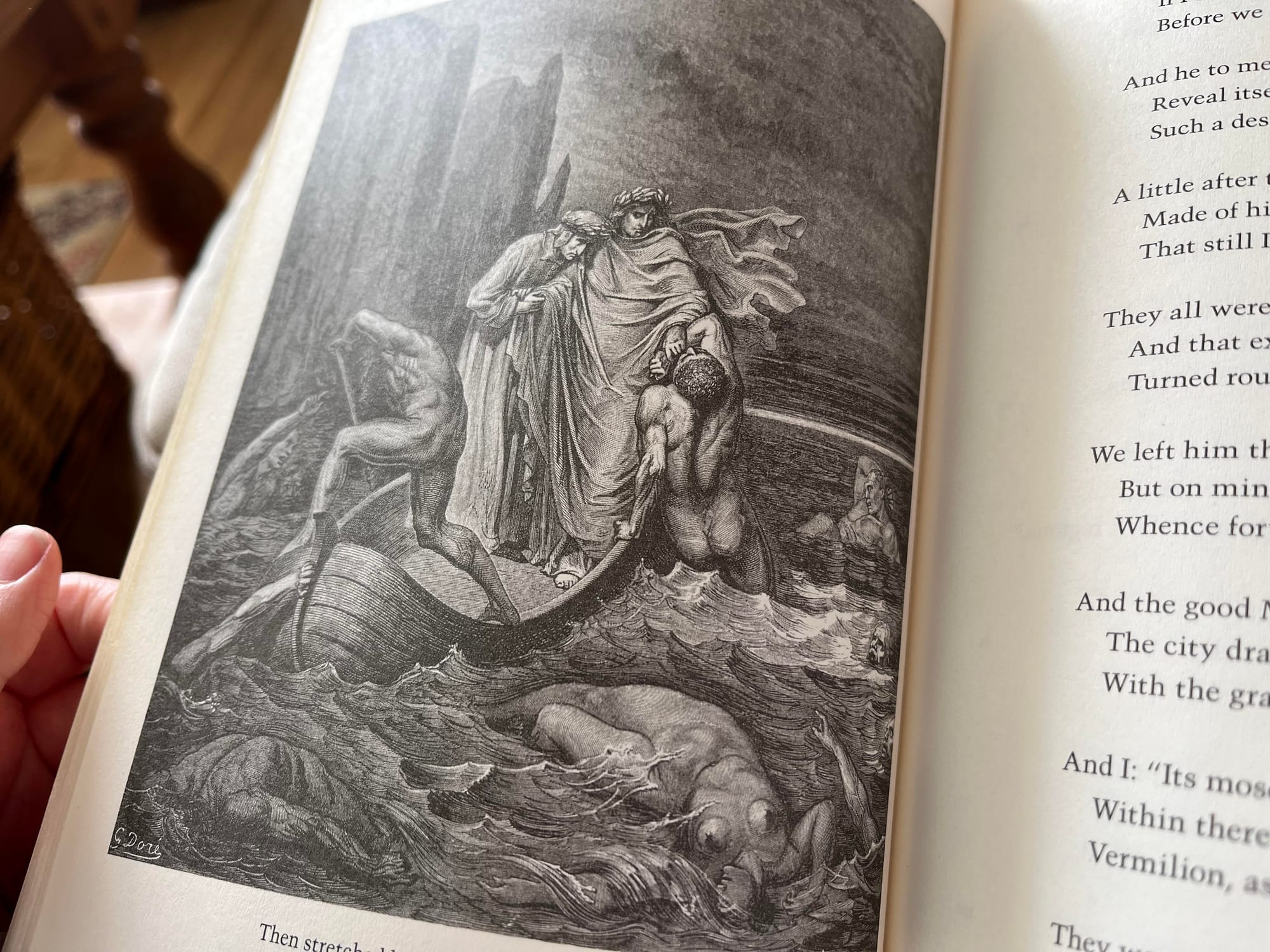

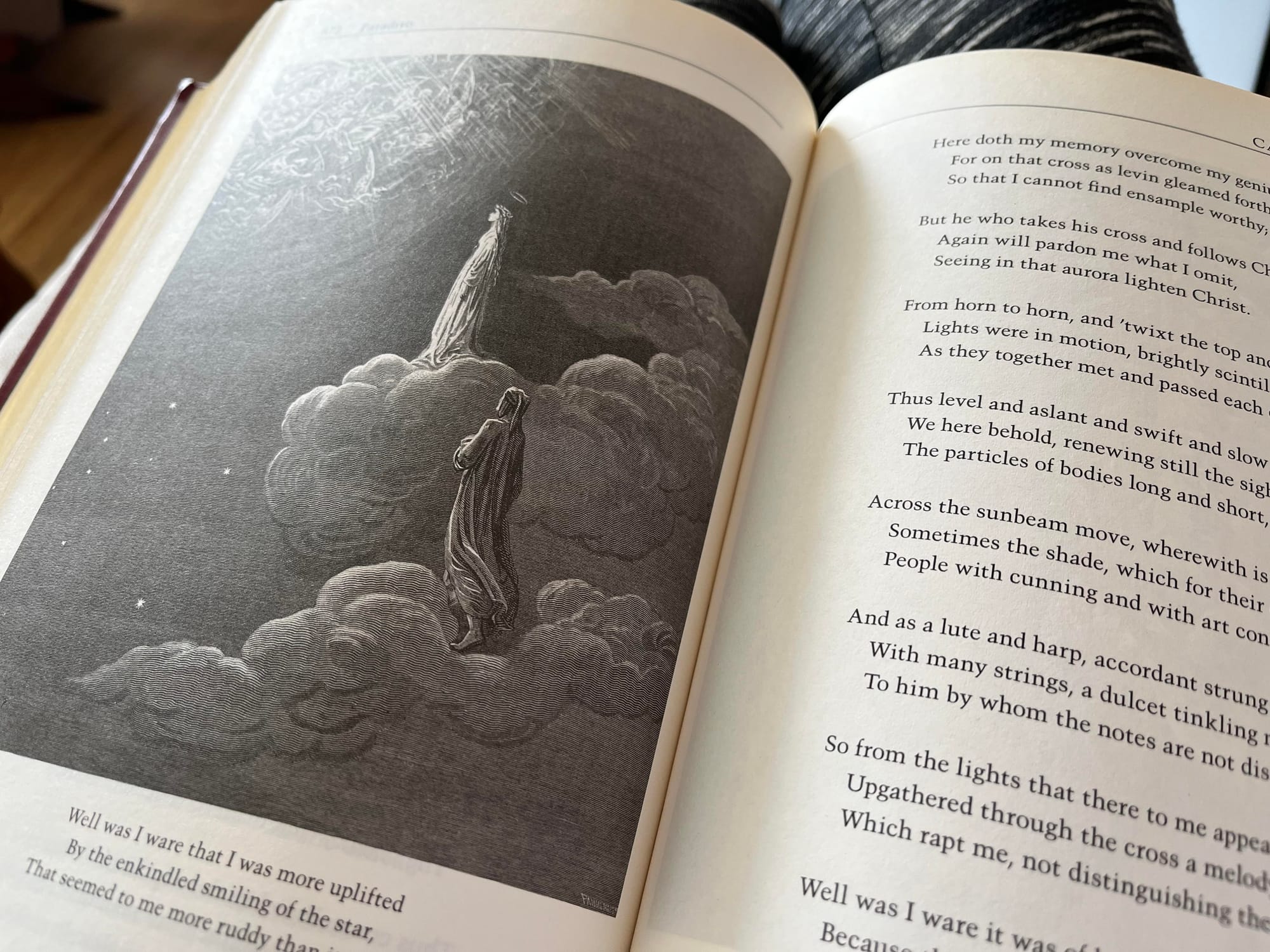

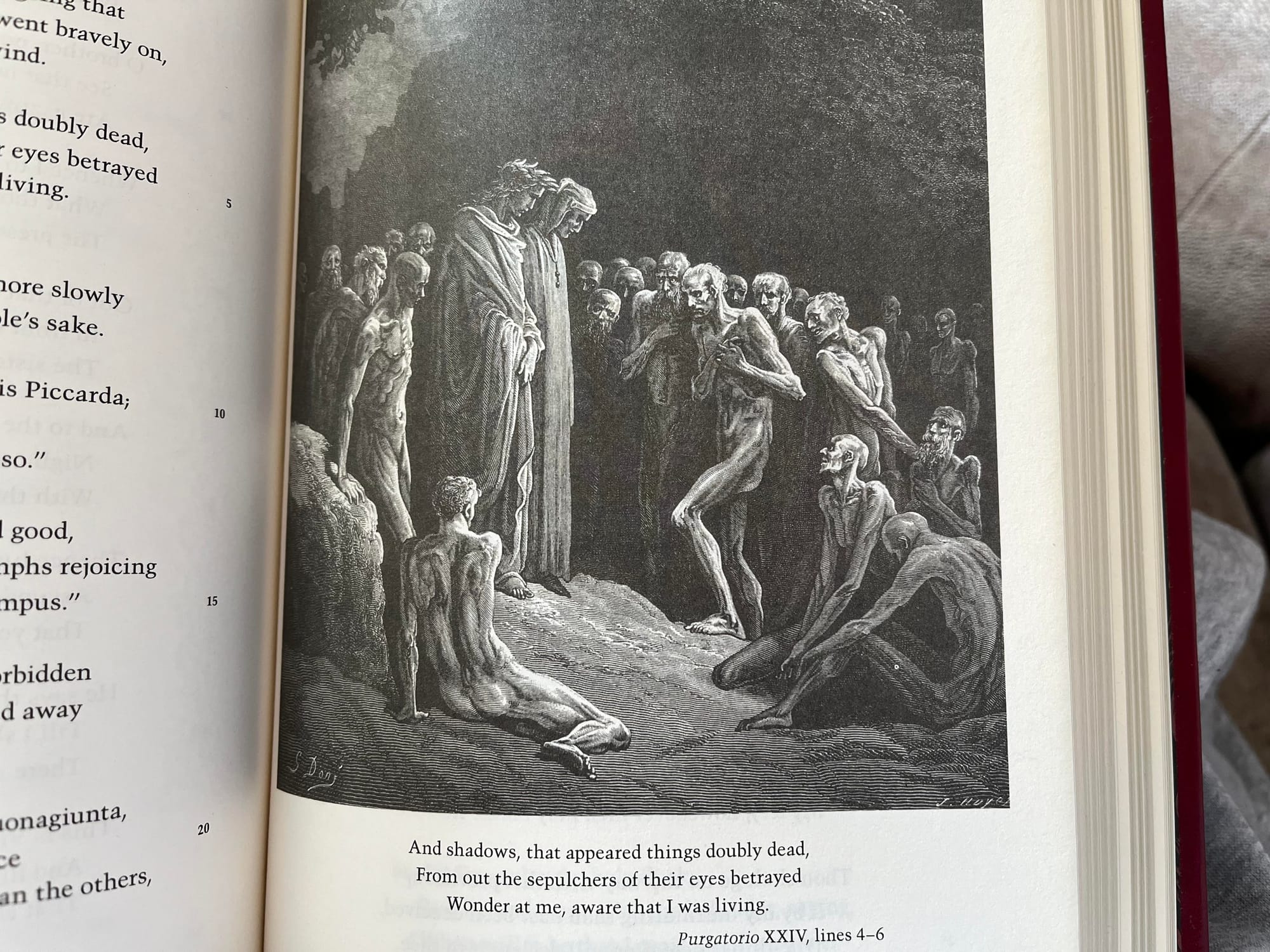

As a quick primer: Gustav Doré (1832-1883) was a French illustrator, painter, printmaker, and sculptor. Known for illustrating works like Dante's The Divine Comedy and the Vulgate Bible, Doré's signature wood-engraving illustrations are dramatic, and particularly suited for apocalyptic literature. Flicking through Dante's The Divine Comedy, you can see why Doré's work lends itself to horror: think piles of naked, writhing people, horrible winged creatures, and angels standing on clouds, gazing at the sun. All captured in dramatic, monochromatic lines.

After chatting to Woods, I wouldn't say that Dark and Deep is inspired by Doré's work, as much as it builds upon it, an addition to a rich canon of work and a continuation of the long-held tradition of building upon the worlds envisioned by other artists.

'There's an interesting thing about The Divine Comedy, which is like, you know, this essentially one person's vision of hell, right? And it's not canonical in any way beyond. It's one dude being like, hey, wouldn't it be crazy ... even in The Divine Comedy, he's referencing Virgil and other artists outside of himself. And so it becomes this infinite, artistic, referential thing. And you know, people from across myth and history are being referenced in that work. So I'm referencing that work that references those works and it becomes, like a big layering, turtles all the way down.'

My experience playing the Dark and Deep demo is that it feels like stepping into Doré's world, as (suitably) dark and twisted as that might be. It feels like finally opening the copy of The Divine Comedy I've had on my shelf for ten years and jumping into it, feet-first, Mary Poppins-style. As the lost and increasingly isolated Sam, you navigate this almost claustrophobic environment, using a magical picture frame to illuminate lost items and find the path forward.

Woods is mostly tackling Dark and Deep solo. 'There's not much company,' he says, although he jokes 'I'm not really a solo dev, I'm working with a dead guy.' Other than the occasional help with animations, models, and illustrations, he's mostly doing it alone. Building on Doré's work is both challenging and liberating. 'It gives welcome constraints ... you know, if I'm making up things, I'm probably doing it wrong. I should be using the work that exists.' He uses the example of creating embers, small flames Sam can use to see in the darkness: 'What does that look like? Okay, well look for energy and essence representations in Doré's work. And the times that he does that are when he's drawing stars, like in Paradise Lost ... or if he draws like Spirit fire coming from heaven. I use the stars from when Lucifer is falling out of the sky.'

Woods views these limitations as a good thing, even if it throws up the occasional technical frustration: 'Doré is an amazing renderer of light, right? He's creating beautiful shading and he's using the density of the lines to do that a lot of the time. And I need to relight everything in my game. So sometimes the lighting doesn't work with the lighting of my world.' This process takes some figuring out, because Woods doesn't feel comfortable messing with Doré's style unless absolutely necessary. 'Sometimes it messes up my vision.'

We talk briefly about other inspirations for Dark and Deep: the podcast itself is inspired by a mixture of NPR podcasts like Snap Judgement, a kind of cinematic storytelling podcast which Woods jokingly describes as 'needlessly dramatic'. The content of the Dark and Deep podcast is, of course, quite different. 'Much more unhinged, Alex Jones conspiracy theory ... the podcaster is a little bit in his feelings all the time.'

I also ask him about his horror roots. He refers to 'the modern age of what they call elevated horror, the A24 stuff. Like Lighthouse or Midsommar, things like that ... I think I've really connected with the modern way, that's all about a particular creative. Like a director or writer that puts their hands in every aspect of the thing. And they tell this really particular story. I like Mike Flanagan a lot. I think Mike Flanagan is probably my number one horror guy.'

The issue that every creative person has to face is the need to promote yourself, and along with it, the need for some kind of validation.

'You get forced into this unhealthy cycle of like, nah, I'll just work on my own and focus on my art and make it the best you can be. And then you put your head up and you're like, oh, shit, I'm scared no-one will care about this. And then you go out and you try to be like, hi, I'm a human and do you like what I do? And then most of them don't give a shit still, or they don't understand it. And then you're just like, well, maybe I'm crazy. What am I doing over here? Can I retreat for another month?'

Woods has been building up 'a community of sorts,' of people interested in playing the game. It's a challenge for a solo game dev to handle, because how do you build and hang onto a community around a demo of a story-based game? 'The hard thing for me is like, everyone's trying to build a community now.' That's partly why he set up Here Below, the overall company designed for game devs with similar sensibilities. 'So people who want character-driven, kind of unique art style, you know, mechanic-focused experiences might like the things that would be under Here Below.'

Aside from the challenges of self-promotion, I ask Woods what this experience has taught him so far. He pauses for a moment to think, then says:

'I teach part-time, my other job is I teach at university level and I teach game development. And my kind of big ask of my students is you need to just make stuff. You don't need to like it. This is an iterative process and you make it, it's not good enough, and you make another thing and there's something about that. That's awesome. One thing I've really learned about this process is though I've always believed this, it's become super apparent that the gatekeeping of the creative process is not necessary, the idea that you can only use a certain tool, and that's the right way to do it. The quote, 'right way', it's a fake idea that prevents people from making things they could go out and do. They actually do cool things with the constraints that they have ... there's 100 ways to make something, you know, and as long as you're making something, and it's good quality, and you're really doing a good job, then I think there's an aspect of ... a lot of people would rather tweak and critique your process. Rather than make things themselves.'

'I definitely ascribe to the perspective that if you're a creative person, you have a responsibility to put out into the world, only the things that you can make, and your art has to go into the world. And if you're spending too much time tweaking, tinkering, it's just not going to happen.'

It's kind of funny timing, because I've been heavily focused on retellings of ancient stories recently; reimaginings of Ovid's Metamorphosis with a focus on modern gender fluidity, for example, and feminist remakes of fairy tales where women emerge as victors, not victims. And I keep thinking about what Woods said in our conversation about using another person's work:

'I don't think you could just use an artist's work without kind of extending and, and continuing the conversation that their work started. And so that's kind of what Dark and Deep is, you know, it's about those themes. It's sort of a modern retelling of a lot of those stories, combinations of those stories. To give it some weight, and makes people think about more ancient ideas and eternal themes than just, you know, whatever this video game is showing you right now.'

I know I'm a massive nerd but I can't help but get excited about this: this innate human need to create, to absorb the work of others and to build upon it, to construct something out of layers that represent hours, days, years of work, pulled from someone else's mind, added to by the minds of others. That's life-giving, purpose-giving stuff. The kind of stuff that makes you feel grateful, and almost duty-bound to join in, if you feel called strongly to something, if something about a piece of work lights a fire in you enough to add your own spin on it. Turtles all the way down, right?

I'm excited to see the full game in August this year, and you should be too: if story-driven indie horror games made with a lot of love are your bag, you should wishlist Dark and Deep on Steam.

Thanks so much to Walter for taking the time to talk to me (you can follow him on Twitter/X). And if you're making a cool thing and you want to talk about it, please get in touch with me!