The End

on dealing with the dead

I want to talk about death.

I keep thinking about it lately. It's the time of year, maybe. Dark evenings, skeletal branches against stark grey skies, the slippery rotting of leaves and conker shells under my feet. There is a stillness in January and February. It feels like nothing at all.

I have made no real plans for my own death, outside of the financial side of things. It bothers me. Every time I sit down to think about specific details, I feel overwhelmed. What songs would I like for my funeral? What would I like to convey to the people I love? How would I make sure my kids get access to my journals when they become adults? Would I want to be buried? Cremated? I'd like a natural burial. The thought of my body slowly and gently returning to the earth makes me feel peaceful, like I'm giving something away in my last moments (aside from my organs, which I would like to donate). But I don't think my children, particularly my youngest, would cope with a burial. A cremation would be easier on them. Also, I'd be dead. So it wouldn't really be about me anymore.

To be clear: I'm not dying (at least, I'm not dying quicker than any other human being). I don't like thinking about death at all. It makes me want to curl up into myself. It makes me feel superstitious. I want to touch wood, to cross myself, to throw salt over my shoulder. The anxiety of it needles away at me.

Weirdly, part of me would quite like to be a mortician. But I can't, because I am massively squeamish. My son has fragile blood vessels in his nose that like to, on occasion, burst spectacularly (usually in the middle of the night. Nothing startles you awake like a child barrelling into your bedroom with blood gushing out of their face). I cannot cope with it. I have to let Chris mop him up while I look the other way, whimpering and occasionally offering useless little reassurances.

Anyway. There's something tender about caring for the recently deceased. Outside of the bodily fluids, I think I'd be quite good at it. I don't think I'd be scared of them. The washing and dressing, I could that. I would talk to them, tell them little things about my day, the weather, the traffic. Things they can't know anymore. And I wouldn't have to worry about making a tit out of myself. The dead are quite forgiving, so I've heard.

I would treat them with care, kindness, and respect. I would see it as an honour to do so. The trouble is, as much as I think I would go home with a sense of relief at having done something meaningful, I might also go home with a broken heart. To work in the death industry means hanging onto your compassion while developing a thick skin. You can't let every death devastate you, or you'd never get anything done.

The obvious paradox about death in video games is that it is both remarkable and unremarkable. You become numb to death, as the protagonist. You can die a hundred times, it means nothing. You can slaughter dozens of enemies in cold blood. They're disposable. But then you hit a key plot point, and another character dies, and there's nothing you can do; their death is different, their death is forever.

There are a lot of games that deal with grief and the aftermath of loss, but not many that deal with the mechanics of death, of the huge network of people that take care of the practicalities. Usually, if there's a mortuary, it's a horror game. There's definitely a shortage of media, in all forms, covering these hidden roles.

I don't think I've ever spoken about A Mortician's Tale on my newsletter. It came out in 2017, way back in the Before Times. It's a sweet, gentle game where you play a mortician, preparing bodies for burial or cremation. Inspired by The Order of the Good Death and the death-positive movement, it received a lot of praise for the way it handles the subject. Given that any mortuary-themed games tend to involve horror, the kindness of A Mortician's Tale is a welcome change.

What you do to the bodies depends upon the wishes of the family; anything from a simple wash to a full embalming or cremation. Afterwards, you can listen in on the conversations between loved ones at the funerals. It's a sweet, and it's sad, but it's also a bit of an insight into the death industry. (Just like any other industry, rampant corporate takeover and excessive greed of the higher-ups is a thing.)

A Mortician's Tale shines a light on the work and care that goes on behind closed doors, but it doesn't deal with the gruesome reality of the job. The flat, cartoonish faces make it far easier to, for example, stitch their mouths closed. It's a deliberate choice, because the physicality is not the focus. It leaves you with an understanding of the emotional care that goes into the job, but not the actual (excuse the phrase) bodily effort of it all.

I start looking into morticians in real life. I watch YouTube videos on it. There's a passion for the job, yes, a drive to be tender to people. But it's so physical. It's heavy, exhausting work, where you're shut away for hours at a time with nobody living for company, and you're left with an aching back and images you can't erase from your mind.

As a child, I developed a terror of death. Not my own: it was the thought of losing other people. I suspect this fear came from the loss of my grandparents on my mother's side, one after the other, while I was still at primary school. I have patchy memories of Granddad, of his deep, rumbling voice. I have more memories of Nan, of her gentle nature. I also remember the day Nan died, and the impossibility of her being there one minute and gone the next.

As a child, grieving was part of life for me. Weekends were spent visiting graves, pouring bottled water over headstones to wipe them clean, and bringing fresh flowers. We talked of heaven, of relatives kicking back with God in the clouds. Even as a teenager, as our trips back to our hometown grew more infrequent, I would talk to my grandparents in my head from the car as we drove away from the cemetery. I'd tell them about my life in our new town, about my friends, my interests, the books I'd been reading. A one-sided catch-up. I wasn't scared of the graves, of the concept of the dead being under my feet. I found it peaceful.

But I was terrified of loss. I developed OCD as a teenager, and most of that was based on the fear of death. The thought of losing my parents would overcome me. I developed insomnia and unhealthy coping mechanisms. I remember when Chris and I were first dating, and during those late-night deep talks that you do when you have entire lifetimes to catch up on, I told him that I was terrified of losing the people I loved. I hadn't told anyone that before. I didn't tell him that certain numbers made me feel better, or that tapping things or switching lights on and off soothed that terror. I didn't tell him that I started to fear his death as soon as I started falling in love with him. I didn't actually think about all this properly until 2020, after a friend passed away in an accident, and everything changed.

I think a lot of people manage to push away the thought of death in their twenties. I didn't think about it for quite a while, really, until my kids were born. Then the OCD kicked in again. I'd have a sudden image flash into my head: what if I fell down the stairs with the baby in my arms? What if I forgot to put the brakes on the pushchair and it rolled out into the road? The huge gamble I had taken only dawned on me once the kids were here. I could not believe how much I loved them, and how vulnerable I felt now that they were in the world with me.

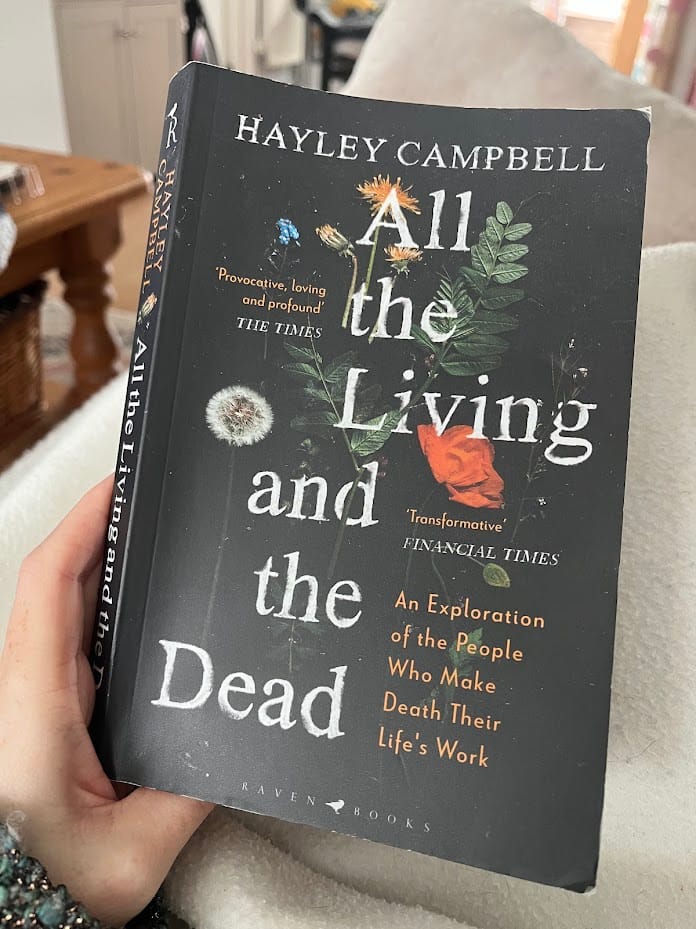

Part of growing up is actually dealing with the difficult bits. The parts that you bury deep down. Halfway through writing this, I decided to keep diving down the rabbit hole, and I ordered All the Living and the Dead by Hayley Campbell. It is remarkable. It's one of the best non-fiction books I've ever read.

In the book, Campbell investigates death. Or, more accurately, what it is like to work with the dead. Unlike me, Campbell was fascinated by death as a child, rather than petrified of it. Her curiosity led her to this project, in which she meets morticians, embalmers, crisis response teams, bereavement midwives, and crime scene cleaners. Often, she gets up close and personal; she helps to dress a dead man in London, stands in a medical facility surrounded by body parts in Minnesota, and watches a grave being dug in Bristol's Arnos Vale. Confronting is a word that I keep coming across in my death investigation journey, and that is something that happens to Campbell again and again. Countless confronting moments that would make anyone wince. She faces it all with curiosity and interest, only to come undone after witnessing a baby in a morgue.

The book is a fascinating look at the vital and difficult jobs that often go uncelebrated; it's also a journey into Campbell's own feelings about mortality, and how you continue when you've seen things that people shouldn't ever have to see. It is beautiful and incredibly sad. It's not often that a book burrows so deeply under my skin that I start considering making different decisions in my own life. I could name a handful, maybe. I wasn't expecting this to be one of them.

It got me thinking about my own feelings on death. Where does the fear come from? Would it have made a difference, I wonder, if I had been allowed to go to my Nan's funeral? I remember stomping my feet in protest as my entire family went without me. If I had gone, would it have helped? Does our societal aversion to death make it easier for fears to fester, to become an insidious undercurrent in a person's life forever? Or does the sadness of loss prompt fear no matter what? Some things are, as Campbell says, 'deeply, bottomlessly sad'. You can't help but be afraid of that.

What is the end result of going down this rabbit hole? I'm not sure. I'm still contemplating whether I'd have it in me to care for the dead or help bereaved families. I have a newfound respect for this work. Part of me thinks I could be part of that process, a cog in the machine, even if it's just making sure that the right flowers have been ordered, that sort of thing. I'm not sure. I'm obviously a sensitive person, and I feel that this could be (and again, forgive my phrasing) a kill-or-cure thing; I'd either find a calling I never knew I had, or I'd be emotionally destroyed by it. I'm not sure if it's worth the risk. Further investigation needed.

But I have noticed something else. I notice death more. I pause when I see a hearse; I'll literally stop walking in the middle of the pavement for a moment. When I'm on the bus, I'll look at the funeral homes and wonder what's happening inside. I used to avert my eyes on purpose, to focus more on the pubs and dental surgeries. I wanted to pretend that they didn't exist, but now I can't stop seeing them.

I'm also noticing life more. Small things. I'll watch a person running down the road with a bag held over their head to ward off the rain. I'll notice a cat lounging under a car and watch it roll around under there, scratching an itch it can't quite reach. I've started leaving my headphones at home so I can listen to things as I walk. The day after I finished the book, my daughter laid across me for a full-body hug, and I couldn't help but think about how simultaneously miraculous and fragile she felt, her body an incredible weave of nerves and muscle and bone.

Recently, I dropped my son off and told his teaching assistant that he'd lost his water bottle last week. 'I know where it is!' his teacher calls, locating it under a desk and holding it in the air. 'I knew it was his, it must have rolled under there.' I smile as I think about this on the way home, walking underneath the trees. A little problem solved.

I think of the network we have built here. The many people that we know and care about. I think about my place here, and about how many connections I've built, the lines branching out from me like a spiderweb: it makes me feel both small and significant. The worries I have about money, about legacy, about making an impact, these things seem less important lately. I'm a bit less in my head, a bit more in the moment. Death isn't less sad, but life feels more precious, and I'm taking that as a good thing. Like most people, I get caught up in the trappings of it all. I worry far too much about what we don't have, what we can't provide, what I'm not doing. When you're worried about paying the bills, you don't really have a huge amount of time for anything else, and you can get caught up in the lack of things.

But really, for everyone, the end result is the same: we're here, and then we're not. Best to be in it with my eyes open, and my mind focused on what's in front of me.

The Ghost of Newsletters Past

This Time in 2024: I talk about leaving Substack's Nazi problem in Moving On

This Time in 2023: I talk about growing up in the shadow of the most beautiful girls on Earth in Olsen Twin Anxiety