Knife Edge

The price of heightened awareness

I’ve been writing down a few things I’m grateful for every day. This is something I’ve been doing over the past year or so, but I’ve decided to do it every morning without fail. It has shifted something in me. I have a deeply burrowed anchor of good things in my life, and that base level of gratitude is useful to have.

I haven’t started the year on an emotional high. I’m actually a bit more fragile than normal. I can tell, because I’ve been waking up at around 11 every night, not long after I’ve drifted off to sleep, with my heart racing and ‘bad thoughts’ flooding my brain. It takes me a long time to go back to sleep, tossing and turning, fighting back a panic attack and worrying, inevitably, about the kids. Worrying that I’m not doing enough for them, that I can’t provide them with the ponies-and-Apple-Watches kind of life that their friends have. Worrying about their emotional well-being. Worrying that I’m not equipped to help them navigate a world that will, by the time they grow up, probably be quite different from the one we’re in now.

I worry about the passing of time, too. The older my children get, the more acute it feels. This sense of time slipping through my fingers like sand, the understanding of time as an unstoppable force that waits for no one. I anticipate the feeling of what is ahead, a kind of preemptive mourning for something I have right now. It doesn’t matter how much I love them and want to keep them with me; they will grow up and leave me one day, and I will have to hold back my emotions and celebrate because the point of parenthood is to get them safely there.

I worry I’m not appreciating them enough as they are.

And I worry that I just won’t remember.

I’ve been playing A Space for the Unbound. I’ll probably go into it in more depth at some point, but something stuck out to me. As the protagonist, Atma can ‘space dive’, essentially diving into people’s minds to solve some kind of emotional blockage.

These are small problems represented as surreal, dream-like moments: a boy struggling with his sense of masculinity, for example, trapped in a cage and surrounded by wolves. As Atma, you can solve these problems by following a series of puzzles. (I can’t tell you how much I wish I could conceptualize my emotional problems as big bad guys I can fight or a collection of items I need to find.)

Early in the game, you dive into the mind of an old man. He stands in a dark landscape, bare except for a broken clock and an old, withered tree. You add an hour hand to the clock, and time starts flying backwards, the tree suddenly heavy with green leaves and plump cherries.

The old man stands up straight. He’s younger, now. In the tree sits a small boy. The old man’s brother. They joke about racing home to their mother. When you leave the memory and speak to the man, he’s heavy with emotion:

‘Brother, oh brother! How I miss you so … but I’m happy … to remember you again …’

As Atma, we have delved into this man’s mind and unblocked his neurological pathways. We allowed the memory of his brother to come flooding back. And now the old man remembers. The price of the memory is the hurt of the loss; his brother isn’t here anymore. He had something, once, and now he doesn’t. But at least we have restored some remnant of the relationship they had.

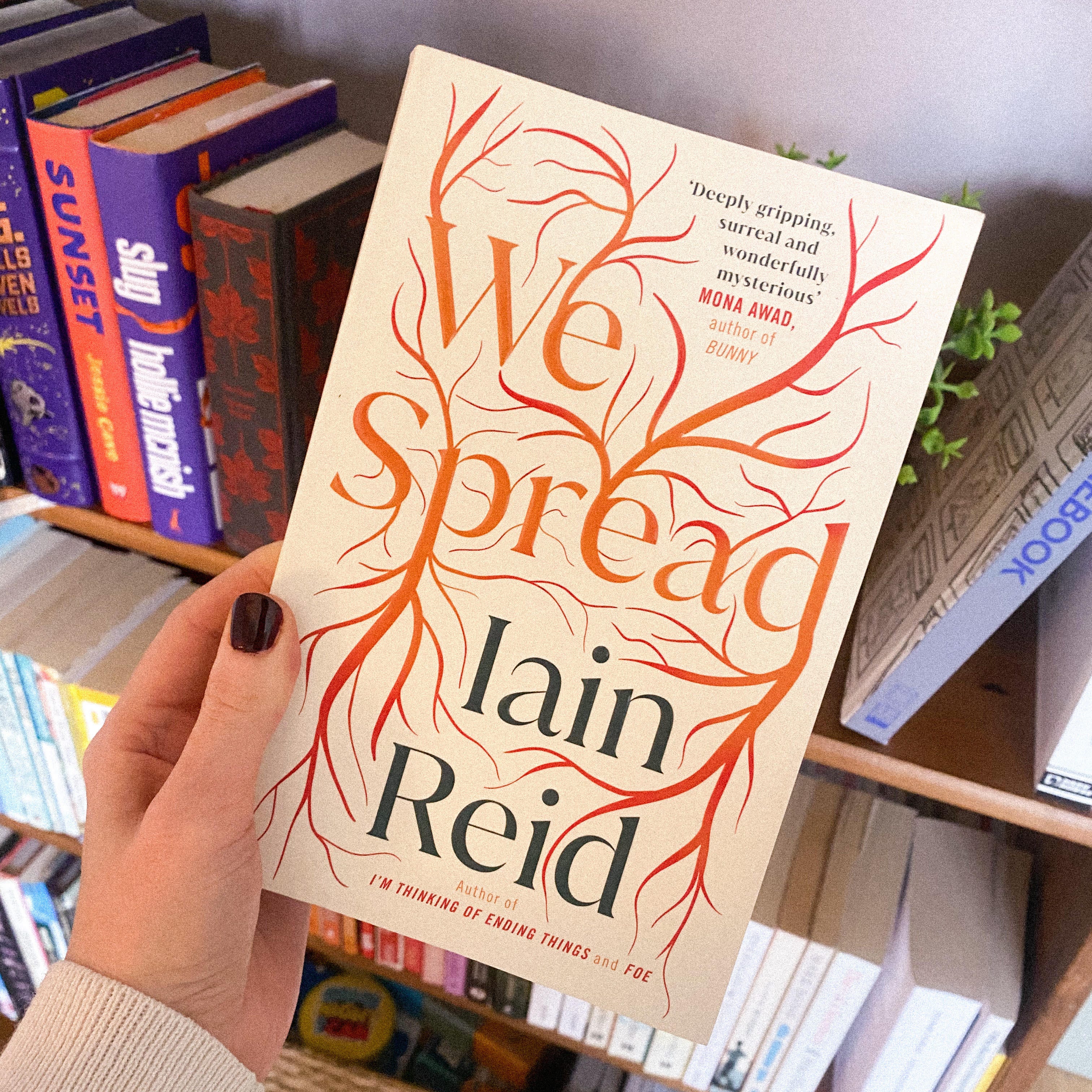

The first book I finished this year is Iain Reid’s We Spread. My husband picked it up for me for Christmas because I loved Foe so much. We Spread is the story of Penny, an artist living alone after the death of her longtime partner. After a frightening incident, Penny is moved into Six Cedars Residence, a small home for the elderly.

Penny is resistant to this change:

“I didn’t ask for this,” I say. “I can look after myself.”

But there’s something strangely soothing about Six Cedars: the large windows with the view of an endless forest of trees, the quietness, the calming reassurances of the manager, Shelley. She starts to build a friendship with her co-resident, Hilbert, a quiet, serious, mathematics-obsessed man.

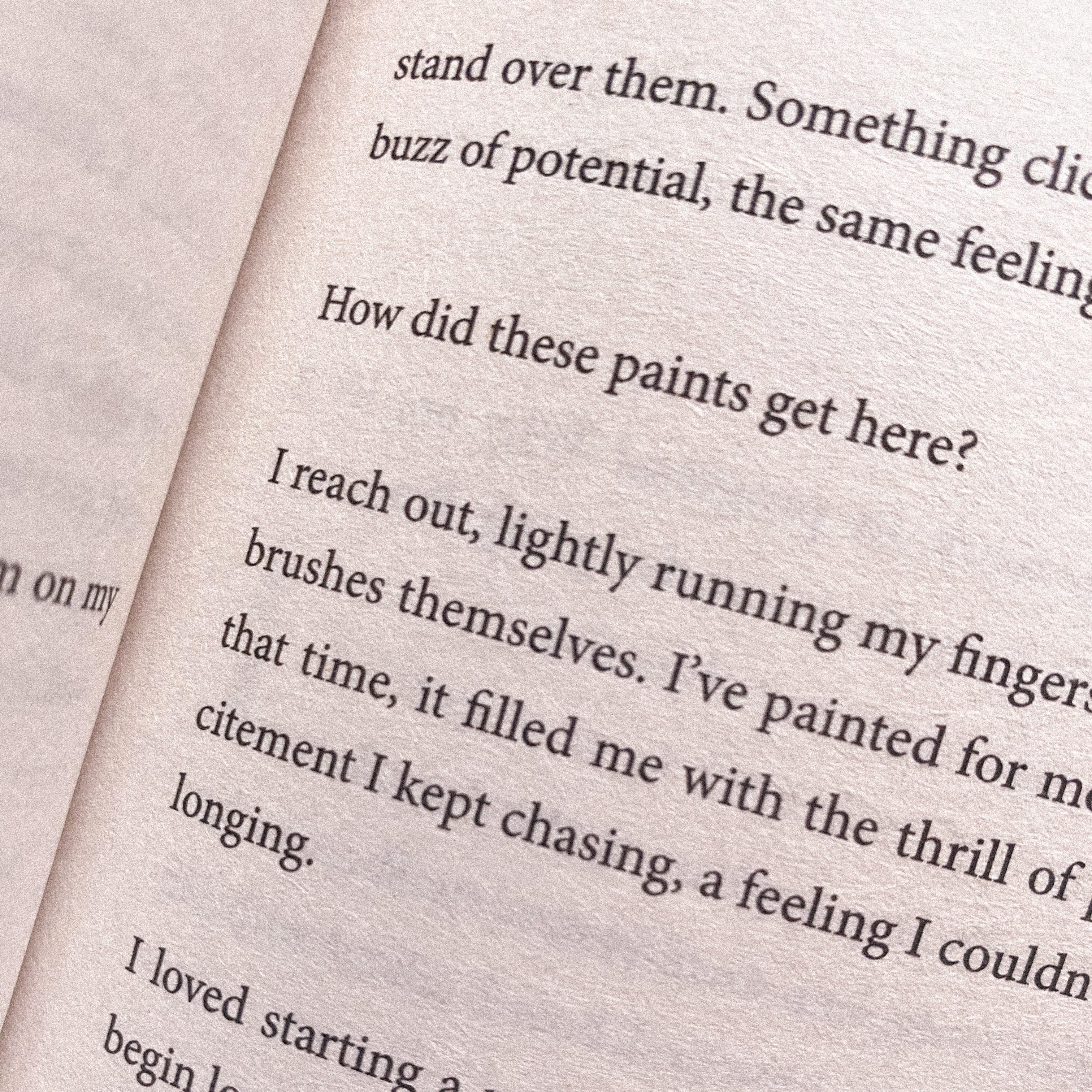

And when Penny starts noticing odd things - the strained relationship between the workers, items appearing in her room without her knowledge, Shelley’s promises of a party that never seems to come - you find yourself trying to settle on a decision. Is Penny starting to lose her mind, or is there something more sinister going on? Is it Penny, or is it them?

As Penny starts to lose the meaning of time itself in the strange and sterile Six Cedars, she tries to delve deep into her mind, to dig further back, to hang onto a sense of herself. And I think this is the frightening thing about getting old: the loss of yourself as an individual, the fading away of a person who has already lived a full and complicated life.

Reid is skilled at writing protagonists with a less-than-optimal grip on reality, and the story has a growing sense of tension and dread that comes to a screaming climax. I spent the whole story rooting for Penny to keep ahold of herself, to hang onto the person she was before she ever set foot there.

Chris and I had a conversation in the post-Christmas lull about our parents. We were driving in the pouring rain. In hindsight, I probably shouldn't have attempted a serious conversation as he attempted to keep us all alive in heavy traffic.

We’re both feeling this weird sense of fragility around our parents. It’s not something we dwell on, necessarily. It’s just an awareness. I hold them for a bit longer when I hug them goodbye. And my parents are quite fit and healthy, they’re just older now.

It’s probably because we know people who have lost their parents quite recently, and we also have a general sense of anxiety around death which developed when our friend passed away in 2020. So much changed because of him. I find it odd that he’ll never know the monumental impact his loss has had on us both, the chain of events that would occur because he left.

This is getting heavy, isn’t it. Having an existential crisis during a global pandemic has fucked me up a bit. I wouldn’t recommend it.

I think sometimes the scales fall from your eyes. Something happens. Maybe it’s a monumental event, like a loss. Or maybe it’s a series of smaller things. Either way, you start seeing life a bit differently. I keep thinking about what Penny says in We Spread:

'What if time was all you had? I say. ‘Maybe if we had all the time in the world, life would start to feel meaningless. Or worse.’

Time is a precious commodity. On the one hand, understanding this unlocks a deep sense of gratitude. And on the other, in the darker moments, it gives me a sense of profound dread. Balancing on a knife edge. I could tip one way or the other.

So I keep my little diary of things I’m grateful for. Every day I write down something. I need to hold onto these memories. Maybe it’s a selfish desire, to preserve my life as though I’m important, as though people will find my life significant in a hundred years. But I don’t think it’s that simple.

Most of my grateful moments involve other people. Sometimes it’s something as simple as giving my husband a longer hug than usual, of running my hands through his hair and knowing that he’ll probably go and get a haircut soon. You know? I know him that well. We found each other and we stayed together. What an amazing thing. And the kids: they do a hundred things a day I want to remember. They are miraculous little things. They won’t always be little and that, in itself, is amazing. I get to bear witness to their growth and watch over them until they’re ready to go.

I am one small part of a bigger picture, one person in a network. What makes my life good, really, is being part of that chain. And I don’t necessarily want to be remembered. I want to remember. I want to grow old and recall what it felt like to be held there, secure, to have a place, to have people to belong to. What a fucking incredible gift.

Maybe I’ll take the awareness even if it does come with a bit of anxiety and pain. Rather that, than numb myself and pretend that time is an endless resource. I can feel myself shifting; my ambitions seem so much less important than they used to, somehow. While I could do with a few less panic attacks at night, I am happy with my small life. It’s enough. It’s more than enough.